“There is no greater power than love and no greater gift than service.” – Frater Achad

School Was My Safe Haven

I was a student who faced some very traumatic experiences. School was my safe haven. In the most compassionate way possible, teachers were the creators of that safe space for me. I loved helping my teachers after school and at lunchtime because it gave me a sense of something beyond myself. In truth, it also gave me a way to deal with the pain of the trauma I was experiencing at home. I wanted to offer that same compassion to other students, and so I became a teacher and then an administrator.

As I grew in the profession, I chose to work in urban schools with students who looked like me and were likely experiencing trauma themselves. The work soon began to take its toll. I was anxious a lot, I felt burned out and tired, and I dreaded going to work. My students’ trauma triggered traumatic memories within me. Before I knew what happened, I was in the middle of full-blown post-traumatic stress disorder, brought on in part because of the secondary trauma I was experiencing. Secondary trauma is a normal occurrence for anyone who works with people who suffer from trauma (Figley, 1995).

I practiced self-compassion to heal. I focused on self-care and eventually left the school site. With intensive healing support, I made a full recovery. Along this journey, I came across the term compassion fatigue.

Compassion Fatigue

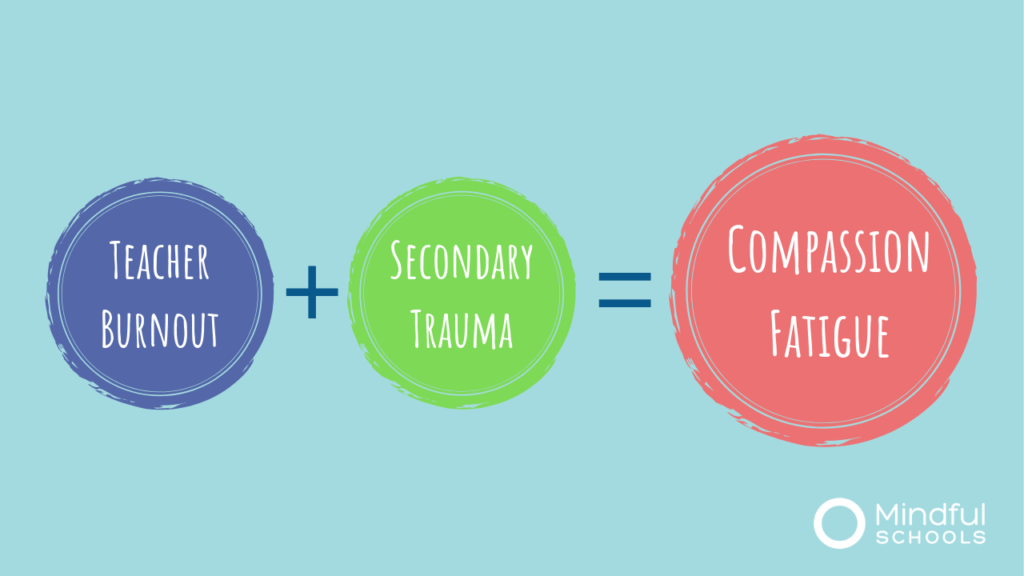

Compassion fatigue is the mental, physical, and emotional exhaustion that comes with working people who are in constant states of distress or trauma (Lerias & Byrne, 2003). Left unaddressed it can cause extreme mental and physical health challenges (Figley, 1995). Stamm (2010), conceptualized compassion fatigue as a combination of secondary trauma and burnout.

I believe that compassion fatigue played a role in my departure from direct student service. If it affected me in that way, I wondered if it was possible that compassion fatigue was causing other teachers to flee the profession as well? What follows is a summary of research aimed at exploring this possibility.

Research on Compassion Fatigue

During my Education Doctorate program, I set out to explore the extent of California teachers’ experience of compassion fatigue. I wanted to know how it impacted their perceptions of school climate and working conditions. And I wanted to know what support systems could be put in place to help?

The Professional Quality of Life Scale, version 5 (ProQOL5) was administered to teachers throughout the state of California, and subsequent follow-up interviews were conducted (Stamm, 2010). The ProQOL 5 measures compassion fatigue in two parts – burnout and secondary trauma, and compassion satisfaction. Compassion satisfaction is the joy one experiences from their work. The sample pool of 100 teachers-participants contained 35% of elementary school teachers, 24% of middle school teachers, 37% of high school teachers.

Here are just a few of the findings:

- Female teachers experience more Compassion Fatigue than male teachers.

- Compassion Fatigue is more acute with beginning teachers than with veteran teachers.

- Teachers working at high poverty schools experience statistically significant differences in compassion satisfaction and fatigue than teachers at low poverty schools. They experience less compassion satisfaction, higher burnout, and higher secondary traumatic stress.

- Secondary trauma from students is not the only trauma teachers are experiencing. Trauma is school-conditions- and climate- based. Parents or school site administration are sometimes the cause. Common threads amongst all interviews were the implication that school administrators do not always understand the teacher’s everyday classroom experience and that parents sometimes feel like an adversary, even though they are not supposed to be.

- School climate and conditions matter. Teachers have concerns about how actions taken by school environment actors including parents, students, other teachers, and administrators affect their ability to create safe and academically challenging environments. Teacher morale is often affected by how students are treated or how students are treating them.

Given that 60% of California’s 6.2 million students live in poverty, 73% of its teachers are female, and newer teachers are often the ones hired to work in understaffed urban schools, we have a big challenge on our hands. My overarching recommendation to address this problem is this:

Compassionate responses and policies that genuinely make a difference in the life of teachers and students should be implemented at the school, district, county, and state levels.

Examples of Compassionate Responses and Policies

- Recognize compassion fatigue as an occupational hazard for educators, especially those who work with traumatized students in high poverty schools.

- Include the development of a course on Compassion Fatigue and secondary trauma in teacher credential programs

- Develop professional development training focused on Compassion Fatigue, educator self-care strategies, adult social-emotional learning (SEL) strategies, and mental health first aid (MHFA) crisis response strategies (National Council, 2015) that support the health and wellbeing of students and staff.

You can find a summary of all of the research findings and recommendations for action in my policy brief entitled: Improving Teacher Retention by Addressing Teachers’ Compassion Fatigue.

Start Your Own Healing Journey

If this research resonates with you and you think this may be something you or someone you know may be experiencing, I offer these recommendations to you:

- Take the Professional Quality of Life Scale. Talk about the results with some you care about. Seek professional support if need be.

- Talk about ways to improve your school’s climate. See the School Conditions And Climate Workgroup Recommendation Framework for suggestions.

- Intentionally show that you care with appreciation for yourself and others. The appreciation should be regular, meaningful, and sincere (Pennington, 2017). I show care with kind words like, “you’re not alone.”

- Attend to your social-emotional needs by adopting practices that support your ability to “effectively apply the knowledge, attitudes, and skills necessary to understand and manage emotions, set and achieve positive goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain positive relationships, and make responsible decisions” (CDE, 2018, p. 2). California’s Social and Emotional Learning Guiding Principles Social and Emotional Learning Guiding Principles could help in this effort.

- Practice mindfulness in and out of the classroom. Mindful Schools has some great resources for educators, you can start with the Mindfulness Fundamentals course.

- Practice self-compassion. These articles on Meeting Self-Judgment with Self-Compassion and Kindness and Self-Kindness have some great tips.

Support and Advocacy

Lastly, this research was designed to help policymakers like school boards, superintendents, and politicians gain an awareness of what teachers are experiencing in all aspects of their work, including those aspects that are unpleasant and born of suffering. I share this with you in hopes that you will sponsor me with your support and advocacy. Please talk about it, share it with your colleagues and administrators, and implement the recommendations that resonate with you. This research shows that compassion fatigue is a real concern for teachers. We all must do our part to help mitigate its effects.

Jacquelyn Ollison, EdD, MEd, is a committed educator with extensive education experience as a teacher and school site and district administrator. She has served as an AVID/MESA Coordinator, Mathematics Teacher, Assistant Principal, After-School Education, and Safety Program (ASES) Coordinator, Vice Principal, and Principal. In her time at the California Department of Education she has supported the development of the California “State-Determined Intervention Model,” currently in use by the School Improvement Grant program. She has co-facilitated and supported the School Conditions Climate Work Group whose recommendation framework was the impetus for much of the recent work focused on school climate in California. She is committed to seeing that all students have access to the best education possible so that they can grow and realize their dreams. She recently earned her EdD at the University of the Pacific with research interests that encompass systems theory, compassion fatigue, school working conditions and climate, the teacher shortage, and teacher retention. Her dissertation is entitled Improving Teacher Retention by Addressing Teacher’s Compassion Fatigue. Currently, she serves as an Education Administrator for in the Performance, Planning, and Technology Branch in the California Department of Education.

References

Figley, Charles R. (1995) Compassion fatigue as secondary traumatic stress disorder: an overview. Compassion Fatigue: Coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized (Psychosocial Stress Series), 1, 1-18. Taylor and Francis. Kindle Edition.

Lerias, D., & Byrne, M. K. (2003). Vicarious traumatization: symptoms and predictors. Stress and Health, 19(3), 129-138.

CDE (2018). California’s Social and Emotional Learning Guiding Principles. Retrieved from https://www.cde.ca.gov/eo/in/documents/selguidingprincipleswb.pdf.

CDE (2017). School conditions and climate work group recommendation framework. Retrieved from https://www.cde.ca.gov/be/pn/im/documents/memo-ocd-oct17item01a1.pdf

Pennington, R. (2017). The Power of Appreciation to Transform Your Culture … and Your Business. Retrieved December 2, 2018 from

Stamm, B. (2010). The concise manual for the professional quality of life scale.

Sutcher, L., Darling-Hammond, L., and Carver-Thomas, D. (2016). A Coming Crisis in Teaching? Teacher Supply, Demand, and Shortages in the U.S. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute.