In a previous article I shared some strategies for finding the time to practice mindfulness formally, and for handling the pressure of a never-ending to-do list. In this article, I explore how to address some of the internal effects of that pressure.

For even when we make time for mindfulness, it can still feel like one more thing on the to-do list. This is one danger of what I call “high volume doing:” a state of continual mental and physical activity driven by the conditions of modern life (our economic system; technology; the media; our culture’s hyper-focus on efficiency, productivity and personal achievement; etc.)

High volume doing sets up a certain frame of mind. We begin to think about and relate to all of life as doing – even activities that are more about being, including mindfulness. When leisure and recreational activities need to be scheduled, their ease and spontaneity become compromised. In extreme cases, one can even start to perceive quality time with loved ones as another thing to do!

Mindfulness is a powerful antidote to this, yet it can easily be subsumed by the culture of doing. The outward danger of high-volume doing is that mindfulness becomes another task, another item on the daily to-do list. The inward danger is that our very minds become shaped by the activity of compulsive doing, such that we begin to relate to being mindful itself as yet another “doing.”

This goes beyond thinking of mindfulness as something to do (“Can I get a sit in before work today?”). It infects our very mental and emotional patterning. We can protect mindfulness from this and use it to counter the effects of high volume doing by being careful with how we think about mindfulness and by refining how we practice.

Protecting Mindfulness

We begin to address the effects of high volume doing by bringing more awareness to our thinking. How much of your day do you spend planning, anticipating tasks, or thinking about the future? Does mindfulness practice fall prey to this habit, becoming yet another thing to slot into the mental calendar?

When you notice yourself planning to “do” mindfulness (or anything else), see if you can pause and attend to the quality of your immediate experience. Is the mind clear and the body at ease? Or is there tension, pressure, anxiety, or rushing? While it’s possible to plan in a relaxed and deliberate way, habitual “planning thoughts” tend to ride on a wave of unsettled emotional energy.

By bringing attention to the quality of our inner experience, we begin to address the underlying pattern of compulsive activity that drives high volume doing, and create the space for something different to happen. Instead of being thrust forward blindly into the next thing, we are more fully aware. We can consider and choose consciously.

marks the beginning a different way of being.

In that moment, we also have the opportunity to reframe our perceptions of mindfulness practice as “doing something.” Instead, what if it were a kind of intimate down-time, a chance to let the incessant activity of life die down for a spell and return to the natural rhythms of the body and mind? How would it be to relate to mindfulness practice as a form of radical non-doing, rather than yet another task?

For while the practice takes effort, energy, and a subtle kind of inner activity, it rests upon the simplicity and ease of being. The more we begin to think about mindfulness in this way, the less likely we are to relate to it through habitual modes of action: to do, accomplish, perform, or achieve.

A Profound Challenge

Correcting our perceptions of mindfulness practice is an important first step, but it takes patience and skill to shift out these modes of doing. When we spend the majority of our time doing things, the mind can lose touch with its natural alertness and its essential capacity for receiving. In effect, our nervous system gets stuck “on” and we forget how to unwind and just be.

This is a profound challenge for the modern day practitioner. The level of stimulation we live with is often so high, and the habit of doing so continually reinforced by our culture, that much of our work in mindfulness practice initially is to relearn how to relax and simply receive experience without falling asleep or zoning out.

“Almost everything will work again if you unplug it for a few minutes,

including you.” – Annie Lamot

High volume doing leaves our nervous system overstimulated and oscillating between two extremes: a kind of hyperdrive, and collapse.

Hyperdrive propels us through the buzzing activity of the day, and plagues us with after-effects like insomnia at night. The momentum of a racing mind continues even when we stop intentionally doing. It’s like riding a bike and pumping the pedals to gather speed. When you stop pedaling, there’s so much energy in the system that the wheels keep spinning!

Collapse is the other side of the coin. There is a biological, if not an existential need for downtime. So without an alternative way to downshift, our nervous system does what it can to get a break. It numbs the overstimulation by tuning out or shutting down: we turn on the TV, browse social media, have a drink, or fall asleep.

A Subtle Kind of Doing

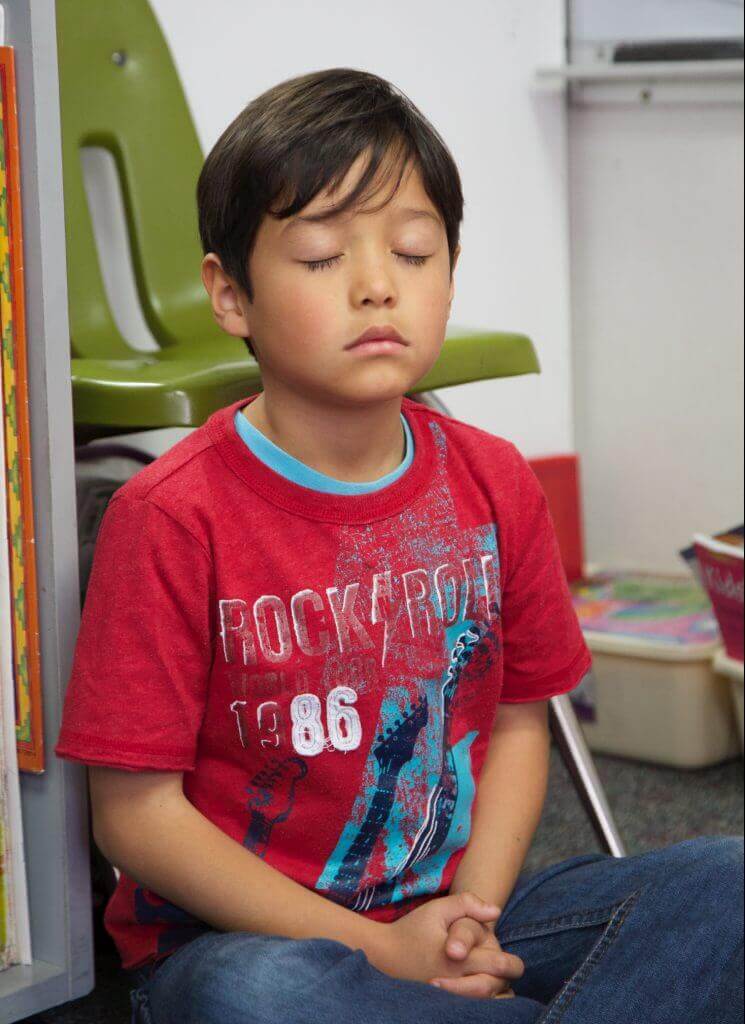

Mindfulness is a place of poise between the over-activation and the collapse. It’s a quiet readiness that is alert without being restless, calm without being dull. In formal seated or standing mindfulness, we use an anchor (breathing, the body, or sound) to tune in to our natural capacity for awareness. We maintain that awareness, allowing the hum of mental activity and the reflexive “doing” impulses to lose steam.

One of things that makes this difficult is that the internal effects of high volume doing are generally pretty unpleasant. When we slow down, a lot of what we feel at first are its effects ricocheting through our nervous system: restless and sleepiness, anxiety and dullness. It requires a certain staying power to bear with the discomfort!

As we become aware of all of this, we may sense the strength and independence of mindfulness itself, an awareness that knows the discomfort but is not affected by it. And as things quieten, we learn how to rest in the innate, receptive quality of our mind. Touching in to this level of being for even a few moments can be deeply refreshing.

I encourage you to experiment with these ideas and tools. How does high volume doing and its effects show up in your own life? In the next article in this series, I’ll discuss how practicing in this way can become a foundation for living with more ease and awareness.