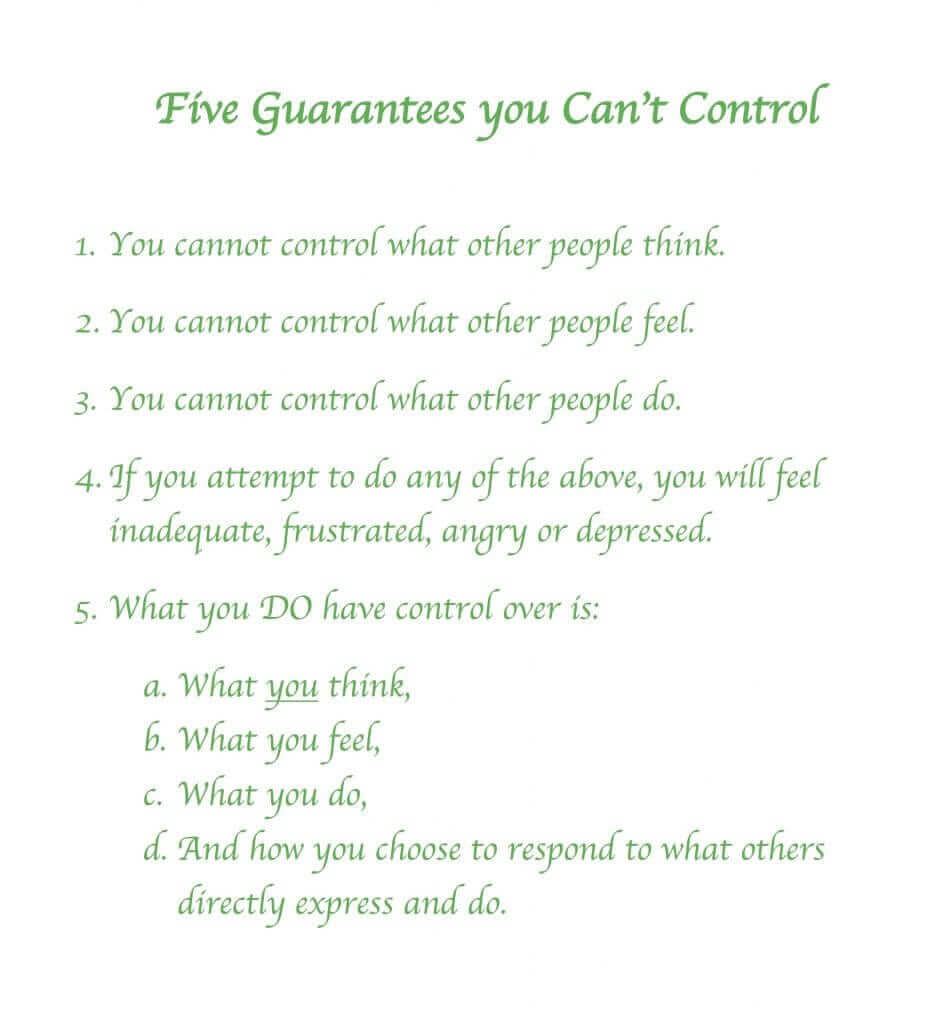

This past week, one educator shared an insightful poster she used in a lesson with tween girls. The poster points out what we can’t control (what others think, feel, say or do); explains what happens when we try to control those things (we feel frustrated, angry, inadequate, or depressed); and, suggests what we can control with the help of mindfulness: our own thoughts and feelings in response to life.

It’s never been my experience… [that I can “control” my feelings]. In the mindfulness trainings I’ve taken, we learn to witness our moods, emotions, feelings, and how they play out in creating thoughts; but we certainly don’t use the word “control.” Over time, experienced practitioners do report a shorter reactivity time (from reaction to response) where they apply mindful self-compassion, say, to the arising emotion. They “appear calm” when in fact they’re just being mindful.

Here’s what I shared on behalf of the Mindful Schools Program team, building on the great discussion that was already happening.

I see two or three issues here, and I think it’s helpful to separate them in the discussion: 1. clarifying the practice of mindfulness, its goals and techniques; 2. the role of agency and ego-strength in psychological development; and 3. perceptions and dangers in word-choice as mindfulness instructors.

The Goals and Practice of Mindfulness

On the first point, as many have shared, the methods and goals of mindfulness clearly are not to suppress one’s feelings in an attempt to control our inner experience. The aim is to nurture a state of curiosity, interest and balance. We ultimately want to give children (and teens, and adults!) the ability to notice however they feel in the moment, and the tools to manage and respond appropriately to their inner and outer experience.

Over time, as we meet our inner experience with caring attention, we find that the inner landscape naturally begins to transform of its own accord. Emotional storms occur less frequently, and with less intensity. Feelings of calm or peace often increase in frequency. The paradox is that this transformation doesn’t occur by wanting it or through willful action. Chasing after a state of calm or struggling to control our inner experience mostly backfires and leaves us feeling worn out and frustrated. Instead, the transformation occurs through being with the very difficult, gritty bits we’d rather not feel!

The Role of Psychological Development

On the second point, we need a certain amount of “ego-strength” —an inner sense of agency and control — before we can let go enough to be with the free flow of our inner experience and emotions. As one educator was saying, what many teens and tweens need the most are tools to help them feel more in control of their inner experience. The key here is understanding (and eventually teaching) that this is not an end in and of itself, because it’s scope and results are limited. That said, if your student(s) don’t feel a basic sense of safety and inner agency, they’re not actually going to be able to practice mindfulness of emotions effectively. Simple attention training techniques like focusing on the breath, sound, or even slow long out-breaths help to build the sense of ego strength and control needed to eventually face our emotions as they are; feel them fully; and digest them.

Choose Your Words Carefully

A lot of the area here is about developing a level of finesse and mastery with word-choice. This really boils down to the context, the skill of the instructor, and the depth of their understanding. Two educators can use the exact same words with entirely different effects based on the audience, the instructor’s intentions, their level of practice experience, etc.

It’s often not in the words, but in how we use them. It’s what we convey through our tone, our presence and attitude. In this way, what’s most required in my view—especially with tweens and adolescents—is a sensitivity to their needs and a deep understanding of the nuances in these realms. When we, as instructors, possess that level of attention, attunement, and clarity, we can use words and concepts like “control” skillfully to support youth.

As our students (be they adolescents or adults) mature in their practice, this initial form of control begins to give way to a kind of inner spaciousness in which their is room for any and all of our experience, just as it is. The mature mindfulness practitioner has access to an awareness that is steady enough to step back inwardly and let go enough to allow the waves of mental and sensory phenomena—agreeable or disagreeable—to simply move through.

This is why Mindful Schools places so much emphasis on the first two foundations of training for educators sharing mindfulness with youth: developing a personal practice, and building skills to teach mindfully. Those foundations then inform our interactions and facilitation with kids as we teach mindfulness.

Graduates of our Mindful Educator Essentials course gain access to our online community of educators sharing mindfulness in their schools and communities. We share resources and engage in rich discussions relevant to teaching mindfulness to youth. (Mindfulness Fundamentals grads share a similar online community focused on the practice of mindfulness itself).

Mindful Schools transforms school communities from the inside out. Founded in 2007, Mindful Schools’ graduates have impacted over 750,000 children worldwide. You can learn more about our online course offerings, Mindfulness Fundamentals and Mindful Educator Essentials.